Read winning team member Miranda Burke’s blog on the Policy Lab here!

After a competitive application round, a group of early career researchers came together in April to discuss how to reduce food loss and waste to contribute to net zero emissions from the food system, each hoping to win the chance to publish a policy facing report as part of URKI discussions around the United Nations COP26 event later this year. Although the 2021 GFS Policy Lab was held remotely due to pandemic restrictions it was no less effective at generating collaborations, discussions, debate and solutions!

The 2021 Policy Lab workshop started with an introduction to the GFS programme by GFS director, Dr Riaz Bhunnoo. Riaz deftly set out the food security challenges and the ways the GFS programme aims to tackle them, including the training of early-career researchers via Policy Labs to provide the skillset to tackle such large interdisciplinary problems. The early career researchers attending this Policy Lab joined from across the whole of the UK and spanned the entire breadth of UKRI’s research remits; from psychology to biochemistry, to economics and animal welfare. This diversity was key in the success of this Policy Lab, generating radical and novel reforms to the food system to tackle the issue of food loss and waste.

Interactive quizzes and activities allowed the virtual Policy Lab to run successfully; one such game involved teams thinking of fantastical, unrealistic ideas to reduce food loss and waste. Proposals ranged from body-scanners at the entrance of shops that would tell you the precise food you needed for the day and not let you purchase any excess, to tables that physically prevented you from leaving if you hadn’t finished your meal. Participants then voted for the idea they liked the most- a pill that made all food you don’t particularly enjoy eating taste delicious! Teams then reformed, representing different food system stakeholders, and were tasked with identifying the positive and negatives of rolling out this pill in their sector. The team who came up with the pill, had to predict the consequences each stakeholder would identify. Ultimately, although the innovators thought of several pros and cons that the stakeholder groups hadn’t, they notably failed to anticipate a lot of the consequences. This whole thought experiment demonstrated the importance of cross-stakeholder collaboration, and the futile nature of food policies which don’t consider the whole food system and all of its participants. This key message on stakeholder collaboration and cross disciplinary approaches stayed front of mind throughout the workshop.

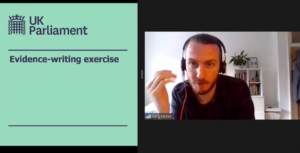

Professor John Ingram from the Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford, launched the Policy Lab talks and provided a superb overview of the food system and the significant impact food loss and waste has on meeting climate agreements. From this sound basis, the attendees went on to hear from Martin Bowman, from FeedBack Global who passionately covered “Why the Climate Emergency Demands Food Waste Regulation” and demonstrated the urgency and importance of developing policy in this area. To enable this, Jack Miller from the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology presented an invaluable toolkit and training session on how to write policy. Taken together, the first day was a powerful reminder of the aims of the Policy Lab and the potential impact it has in COP26 discussions.

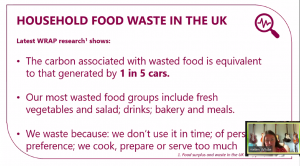

On day two, attendees were taken on a journey through the food system, hearing from different stakeholder perspectives and exploring the range of causes of food loss and waste. The teams first explored the role of innovative technologies in reducing food loss and waste, including apps to distribute unsold food, packaging with precisely monitored atmospheres to prevent spoiling, and cameras in your fridges to report what food needed eating. Attendees heard from Professor Carol Wagstaff, from the University of Reading and lead in BBSRC’s Horticultural Quality and Food Loss Network,

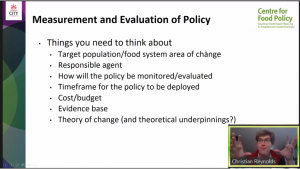

who discussed how to maintain food quality and nutrients through food supply chains. Helen White from WRAP, provided staggering statistics on food waste in homes and the role of WRAP in generating this data which generated an excellent discussion. Our final speaker was Dr Christian Reynolds from the Centre for Food Policy at City University London who reviewed the effectiveness of current food loss and waste policies, and what the UK could learn from other countries. This was a brilliant and inspiring talk to end on, in part because Christian was returning to speak at the GFS Policy Lab after being an attendee at the same event a few years earlier!

The Policy Lab talks were interspersed with workshop sessions, allowing attendees to debate and discuss with each other and interact directly with the speakers.

Towards the end of the Policy Lab, attendees discussed and began to formulate ideas for their report pitches, branching off into teams. By the end of the 3 day workshop, attendees had developed some excellent and innovative proposals that directly tackled different causes of food loss and waste, and had been thoroughly researched and referenced. After going through several rounds of peer review we shortlisted the reports and announced the winning team, who are already working on their report- stay tuned!

Winning report: A New Era: Can True Cost Accounting Remove Siloed Thinking about Food Waste?

Shortlisted report: Too little time to waste: Addressing citizen’s time availability as a barrier to reducing the environmental impact of household waste to meet climate emissions targets.

Shortlisted report: There’s an app for that: shortening food supply chains and reducing food loss and waste through the innovative use of technology on a localised scale.