How can we nudge people to eat more healthily and sustainably? University of Cambridge’s Arianna Psichas reports from the Global Food Security programme’s Policy Lab on sustainable nutrition.

As the child of someone who has spent their career working in environmental policy, I have grown up with an acute understanding of the many challenges our planet faces, particularly with regard to climate change. Now, as a nutritional scientist I am passionate about public health, and I know that a shift towards more sustainable food options can very often also be healthier.

When I saw the email calling for applications for the GFS Policy Lab, I knew I had to be involved. The policy lab aimed to introduce early career researchers from different disciplines to the challenges facing the wider food system, with funding available for exciting new ideas.

Day 1: the Challenges

Fast-forward to a rainy Thursday in January, I found myself in a room with an impressive array of early career researchers including, among others: a mathematical modeller, a food security expert, a consumer behaviour specialist, a microbiologist with a passion for urban agriculture, a food technologist and a livestock vet. Thankfully, as a group of just twelve, it didn’t take long for the nervous energy to turn into an excited buzz.

With the ink beginning to dry on the Paris Agreement, the first ever legally binding global climate deal, how will the UK achieve its commitments? Day 1 was about the challenges, which were vividly set out for us by a series of experts, including GFS Champion Professor Tim Benton.

Most people are aware of the detrimental consequences of greenhouse gas emissions (GHGEs) on climate change, but how many people know that the food chain is responsible for a whopping 30% of them? If you’re going to start reducing emissions, you might as well start with food!

However, what would this actually look like in practice? What are the implications and barriers for producers, consumers and the wider food supply chain?

Day 2: the Solutions

Day 2 was all about the possible solutions. We discussed and debated, encouraged by a range of thought-provoking activities. The more I talked to people, the more I felt a growing sense of ambition and potential developing in our ideas.

Much to our dismay though, it turned out that we the participants, who all work in related areas, had very little idea of the carbon footprint of individual food products. We knew about the carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions associated with red meat (12.1Kg of CO2 per kilo of beef versus 2.6Kg per kilo of chicken) but what about rice or asparagus? A chocolate bar? If we don’t know, how can we possibly expect the public to?

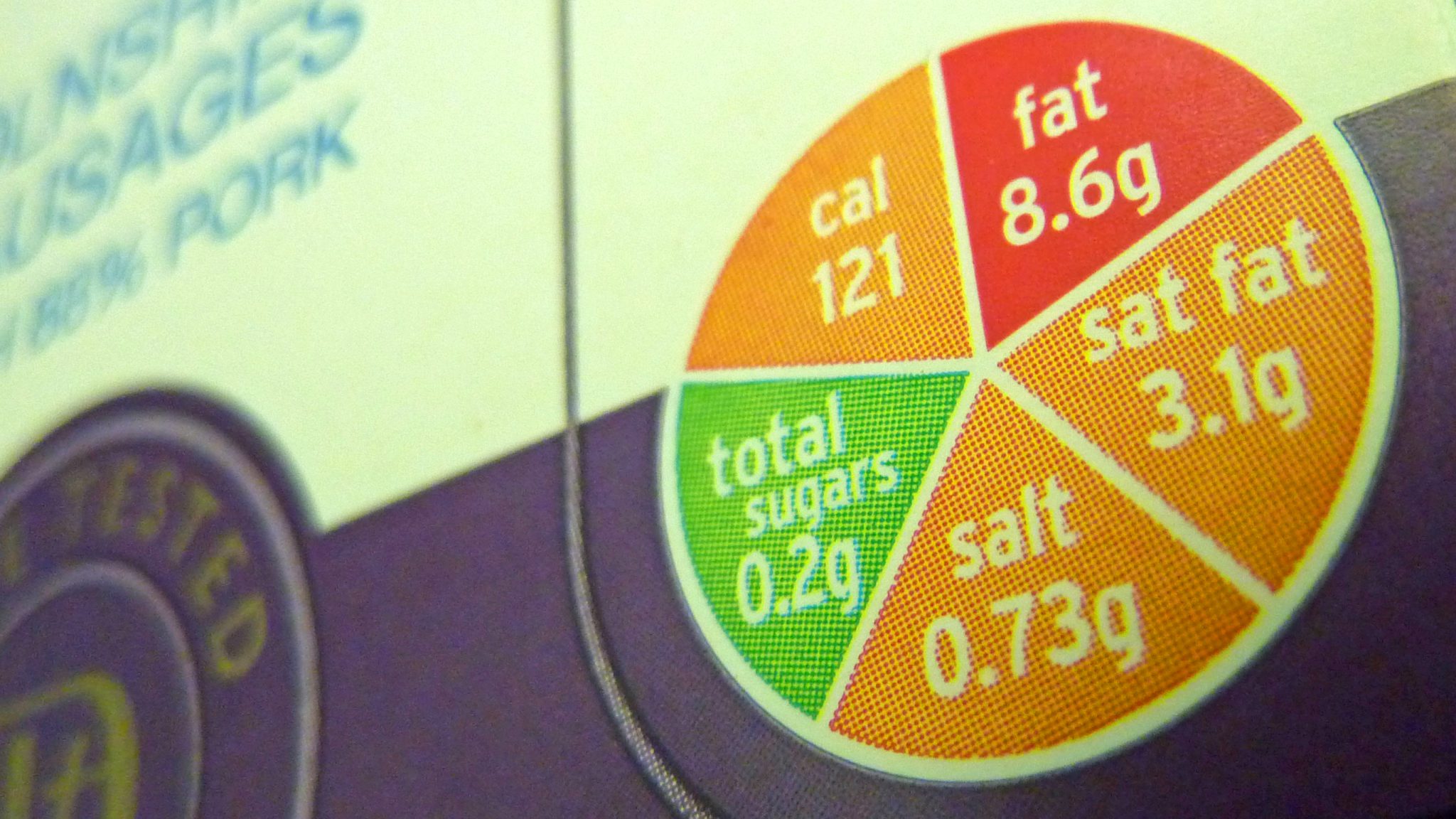

I know all too well how many calories are in some of these products of course; the saturated fat, sugar and salt content, but this information has become quite difficult to avoid, so you don’t have to be a nutritionist to recognise a healthy option from an unhealthy one. It’s staring us in the face in the supermarket, and the traffic light signs are pretty clear: red=bad, green=go for it.

When it comes to the environmental impact of food though, sadly, it’s still too easy to be blissfully ignorant as a consumer, tucking into a fillet steak. And let’s face it – it’s exhausting trying to keep up with the information overload surrounding food.

So how do we empower consumers to make better informed decisions? My team proposed to encourage a change in consumer behaviour towards a more healthy and sustainable diet by devising a new method to raise awareness of the carbon footprint of food.

The idea was to visually convey this information at point-of-purchase (i.e. at self-checkout in-store, and online), using a carbon footprint traffic-light system (such as found for salt, sugar and fat levels in the UK) which would pop up on the service screen and highlight more sustainable and equally nutritious alternatives.

Unfortunately, increased awareness alone often isn’t enough to drive behaviour change. Price, on the other hand, is one of the strongest factors influencing consumer choice. So it’s simple really: sustainable food must be cheaper than unsustainable alternatives.

Therefore, we also proposed to evaluate the impact of showing consumers how a shadow ‘GHGEs tax’ (shadow meaning illustrative rather than an actual tax) may alter the cost of food items, perhaps starting with the meat sector as a case study. (In November, think tank Chatham House recommended a tax on meat to mitigate climate change.) If the environmental cost of food production is highlighted in monetary terms, this might encourage behaviour change. Working with a range of stakeholders will be essential and our idea will almost certainly evolve as the project progresses.

What I gained

The workshop opened my mind to thinking about the wider picture. I learned a tremendous amount, I met brilliant people with whom I will remain in contact, and I had the chance to be part of a stimulating and creative process. Our project has now been given the go-ahead for funding by GFS and I can’t wait to get started.

It is now more crucial than ever that we start to think like global citizens, share in the outrage about the state of the planet and play our part in driving the change we want to see. Especially for early career researchers like myself, it is imperative to think beyond what goes on in the laboratory or the field, to foster cross-disciplinary dialogue, and to consider our work in the context of policy – because policy matters.

I can’t praise the GFS Policy Lab workshop enough; hopefully its outcomes will encourage the programme to repeat this in future so that more researchers can gain this valuable experience. Lastly, I hope that our future report will help to highlight the urgent need to raise awareness of the environmental impact of food and demonstrate a new way of shifting consumers towards a more healthy and sustainable diet.

About Arianna Psichas

Arianna Psichas is a research associate at the University of Cambridge, working on intestinal nutrient-sensing in the field of obesity and diabetes. She has a PhD from Imperial College London and an MSc in Nutrition from King’s College London.

Really good to see young researchers engaging with wider food security issues – well done GFS for supporting this! And an enjoyable blog post too. My question is how much will a reduction in food related GHGs help us to meet the Paris target of 1.5C? Could it do it on its own and if not what %?

In answer to William’s question:

If we fed less grain to livestock (and therefore ate less intensive meat), and were we to reduce waste and loss as much as possible and to eat wisely in amounts, there is the potential to make significant savings in emissions (up to half, from a back of an envelope calculation). If this freed up land which was used for biomass carbon capture and biofuels production it would get a very long way towards making Paris possible – especially with the existing and acknowledged potential for clean energy.

Thank you for your comments William, and thanks for your answer Tim! I just wanted to add that according to the Chatham House report mentioned in the blog post, a global reduction in meat consumption alone could bring a quarter of the emissions reductions required to meet the 2oC target.

Hey Arianna

Id love to chat more about this subject, could you drop me an email on thomasmicklewright@gmail.com to discuss? Im looking at the best tools to influence government to reduce animal protein consumption

Thanks Tom :)

Hi Tom. I would be happy to discuss this subject further and it would be great to hear about what you’re working on. Please see my LinkedIn reply.

How about an app that displays the product info when you photograph it on your smartphone (maybe through bar code/QR code). This was done with the microbead campaign to help consumers check which products contained the microbeads. It helped those of us who wanted to make a change but didn’t have all the info to hand when shopping.

Thanks for your comment Lily, that’s a very interesting concept. It would definitely be a useful tool! As you alluded to though, it wouldn’t necessarily reach those who aren’t already aware of the problem and want to make a change.

Hi Arianna

Very interesting reading thanks.

I am working on a project in sustainable seafood, bringing fish into London via RailFreight, and analysing the best way to educate consumers, not only about sustainable fish, but sustainable supply chains too. Fish and seafood is behind meat production in teenaged labelling and awareness, we have vast unexploited natural resources in UK to bring to customers in sustainable way.

Hi Cara

Thank you for comment. Sounds like a great project to be involved with. Improvements in awareness and food labelling in this area are definitely needed (as is an increase in the availability of sustainable products!). It would be very interesting to hear about what you identify to be the best ways of raising consumer awareness.