Blackouts and water shortages can severely harm a nation’s food security. Resource allocation tools can help policy makers improve energy access while minimising hunger, says the Stockholm Environment Institute’s Louise Karlberg.

Last July, Zambia found itself in the midst of a crippling energy crisis caused by low water levels in the reservoirs for hydropower generation. Load shedding (cutting off supply to parts of the power grid) became the norm, sending politicians into a frenzy because electricity is the lifeblood of the economy.

The blackouts had many negative knock-on effects for food producers. For example, while some large-scale poultry farmers were able to switch to alternative energy sources, such as generators to power vital equipment such as refrigerators, many of their smaller-scale fellows were unable to make this investment and lost income. And dairy farmers were faced with a range of other challenges related to the load shedding, as their plants can take several hours to regenerate after each power cut.

Of course the lack of rainfall meant there was also less water for farmers. While there is a general need in Zambia to increase irrigation to bridge droughts and dry spells and improve yields, in cases like this irrigation would be in direct competition with hydropower generation for any stored water.

Power cuts today or a poor harvest next month – which is worse? Similar dilemmas face countries all over Africa.

Divided we fall

These dilemmas cannot be ignored. Much of Africa is attempting a major transformation of both the energy and agricultural sectors – which are relied on as cornerstones in the development visions of several national policy frameworks. Water is one of the main resources underpinning these transformations, alongside availability of land and nutrients, for instance.

SEI research in Ethiopia, Zambia and Rwanda (PDF) on how these sectors are evolving together highlights a common message: if different sectors rely on substantial quantities of a common and scarce resource – in this case water – they need to talk.

In Africa’s energy and agricultural transitions, there will inevitably be trade-offs over water, and at the same time potential synergies to tap into. Plans and policies in both sectors need to take into account competing resource needs and agree on allocations and priorities. Otherwise there is a real danger they will clash, and livelihoods, well-being and long-term development will suffer in the process.

However, today policy-making and planning commonly take place within sectoral silos. This is not always a bad thing. It may even be preferable where resources are not in short supply and are used sustainably, since adding complexity is both costly and time-consuming. But this is not the case for water in much of sub-Saharan Africa.

How to work together

One starting point for this kind of inter-sectoral coordination is to carry out joint assessments of the common resources available. Today, such assessments are rarely done because of a lack of data and the capacity to analyse it.

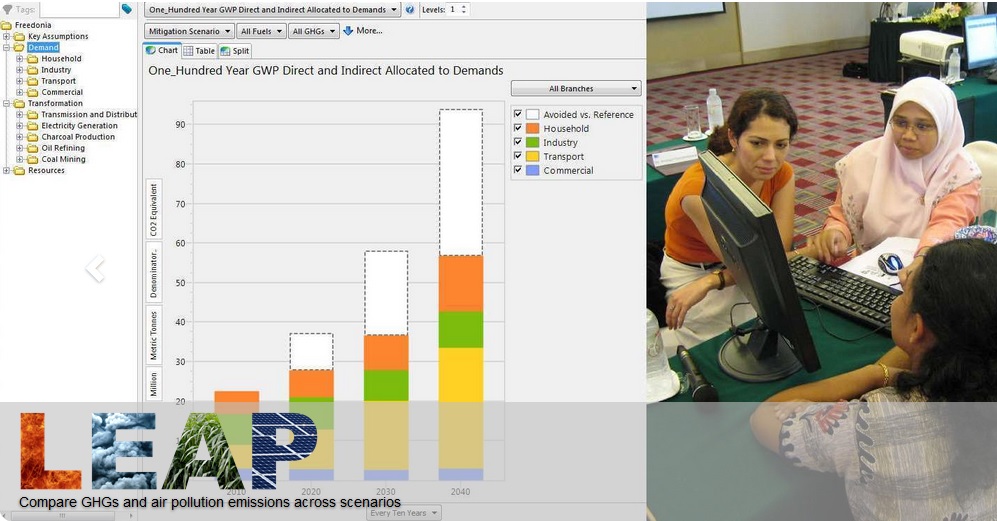

But two user-friendly planning tools developed by the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) can help, not least because they can still deliver robust results when data is limited: the Long-range Energy Alternatives Planning system (LEAP) and the Water Evaluation and Planning system (WEAP).

To apply these tools, SEI research teams and planners generate resources allocation scenarios for food and energy production, working closely with a broad set of stakeholders. These scenarios are applied in the tools to assess how they might play out in terms of water availability and energy production.

Once the assessments have been done, there is a need for practical answers. The outputs from the tools can be used to inform dialogue between sectors to find the most mutually beneficial options.

Exercises like this can encourage new thinking, such as seeking renewable energy sources less reliant on water than hydropower. For example, generating biogas from agricultural waste means agricultural development actually supports energy development instead of competing with it.

Similarly, investments in the right sanitation and wastewater management systems could produce biogas or solid fuels, while also making water and plant nutrients available for farming.

In Africa’s (hopefully sustainable) energy and agricultural transitions, dialogue between development sectors will be crucial.

About Louise Karlberg

Louise Karlberg is a senior research fellow and acting Stockholm Centre director at the Stockholm Environment Institute in Sweden.