Can we tap into ecological defences to better protect crops? The University of Sheffield’s Will Buswell reports.

Crop pathogens are a substantial drain on world food production. Annually, an estimated 20% of global yields are lost to disease, but this figure belies far greater losses for specific food systems and the people whose stable existence is dependent upon them, particularly in developing countries.

For instance, rice is the staple crop for over half of the world’s population, yet almost 40% of yield is lost to disease each year.

Current efforts to mitigate disease losses are worryingly over-reliant on the use of pesticides with significant economic and environmental costs, or the development of pathogen-resistant crop varieties, which can take decades. Even where effective disease control exists, the combination of rising temperatures and unpredictable weather events could accelerate reproduction of pathogens or their vectors, increasing the likelihood of pathogens evolving resistance.

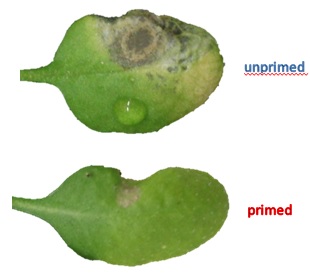

An under-investigated approach is that of utilising the crop plant’s innate immune system to resist pathogen attack. More specifically, the innate immune system can be sensitised or ‘primed’ to respond more quickly and strongly upon detection of pathogens, thereby better protecting the plant against attack.

Prime numbers

The range of so-called ‘priming’ techniques are inherently interesting as crop protection tools for a number of reasons.

Firstly, priming can be triggered by a wide variety of direct physical stimuli, from plant-derived chemicals to symbiotic micro-organisms. For instance, many soil-borne fungal and bacterial species naturally form associations with plants that result in priming of immunity, alongside co-benefits of enhanced nutrient uptake and enhanced soil stability.

Thirdly, multiple genes are typically involved (PDF) in coordinating these primed immune responses, lending a higher degree of evolutionary durability than seen with pesticides or resistance-genes.

Finally, whilst chemical priming agents and specific priming genes may still be patentable, there is likely a weaker legal case for intellectual ownership of the innate ability of a plant to prepare itself for subsequent pathogen attack. Defence priming may therefore be appropriate for all those in need of it, rather than only those who can pay for it.

Looking ahead

There remain several obstacles to the wide-scale integration of plant defence priming into agricultural practice, such as inferior performance in comparison to pesticides and the variability between crop varieties in the strength of their primed defence responses.

In addition, over-priming of plants can result in plant growth costs, which would undo the benefits of protection against pathogens. However, a strategy of using priming in combination with reduced pesticide use can enhance protection, and help to meet commitments on reducing chemical inputs to agriculture.

I believe that the evidence I have discussed should prompt greater consideration for defence priming as part of an array of future disease-prevention tools – a cause you could even consider yourself ‘primed’ to support…

About Will Buswell

Will Buswell is a 1st year PhD student at The University of Sheffield, working in the research group of Professor Jurriaan Ton. His long-term research and career goals are to improve the durability and equitability of food production systems, both through better design of agri-technologies and working on a better framework for their distribution.

thanx ur report is good and very useful fo preparation of my Ph.D. course seminar