Terrestrial and aquatic food production systems share a range of common problems that need solutions. Rachel Norman from the University of Stirling reports.

A mathematical biologist by training, I was very keen to tease out whether we could treat fish and crops as being the same when we come to think about problems in food security.

After some consternation amongst my biological colleagues, there was consensus that aquaculture systems share some common features with both crops and chickens – they both have relatively high stocking densities, for example. They also share common risks, for example disease outbreaks can be devastating in all cases.

However, intensively farmed chickens differ slightly in that their environment is often more controllable. So we focussed mainly on the links between crops and fish, discussing the idea that soil is to plants what water is to fish.

Over 2015-16 we brought together a range of researchers, policy makers and stakeholders from crop, capture fisheries and aquaculture systems in a series of workshops, held at the Scottish Universities Insight Institute, designed to allow the three production sectors to share information and ideas.

What came out of these discussions was the identification of areas where there is a direct and important interaction between terrestrial and aquatic systems. There are also common problems faced by the different production systems which mean that they could work together to find solutions.

On the limit

One of the limitations to the growth of the aquaculture industry globally, and in the UK in particular, is the need for sustainable source of feed for the fish. Many of the fish species which are farmed require fish meal and fish oil for optimal growth and this is a limited resource. A great deal of research has gone into developing replacement feeds which use, for example, plant-based substitutes.

So how do we optimise healthy diets and protein production if we are feeding crops to fish instead of directly to people?

This brings out one of the most obvious direct links between aquaculture and plant systems. The Beans4feed project, for example is investigating the use of fava beans to feed pigs, poultry and salmon. Another example of this link is the Camelina project in which a genetically modified crop has been engineered to produce omega-3 fish oils which could be fed to fish.

Of course this question of feeding crops to livestock is much broader than fish with, for example, 40% of cereal in the US (PDF) being used for livestock feed.

In my world of asking “why are plants like fish?”, the equivalent issue of sustainable feeds to fish is fertilisers for crops, in this case it is nitrogen and phosphorus that are the limiting resources. With ‘peak phosphorus’ looming, we need to develop ways of reducing losses and recycling these nutrients more efficiently.

All change

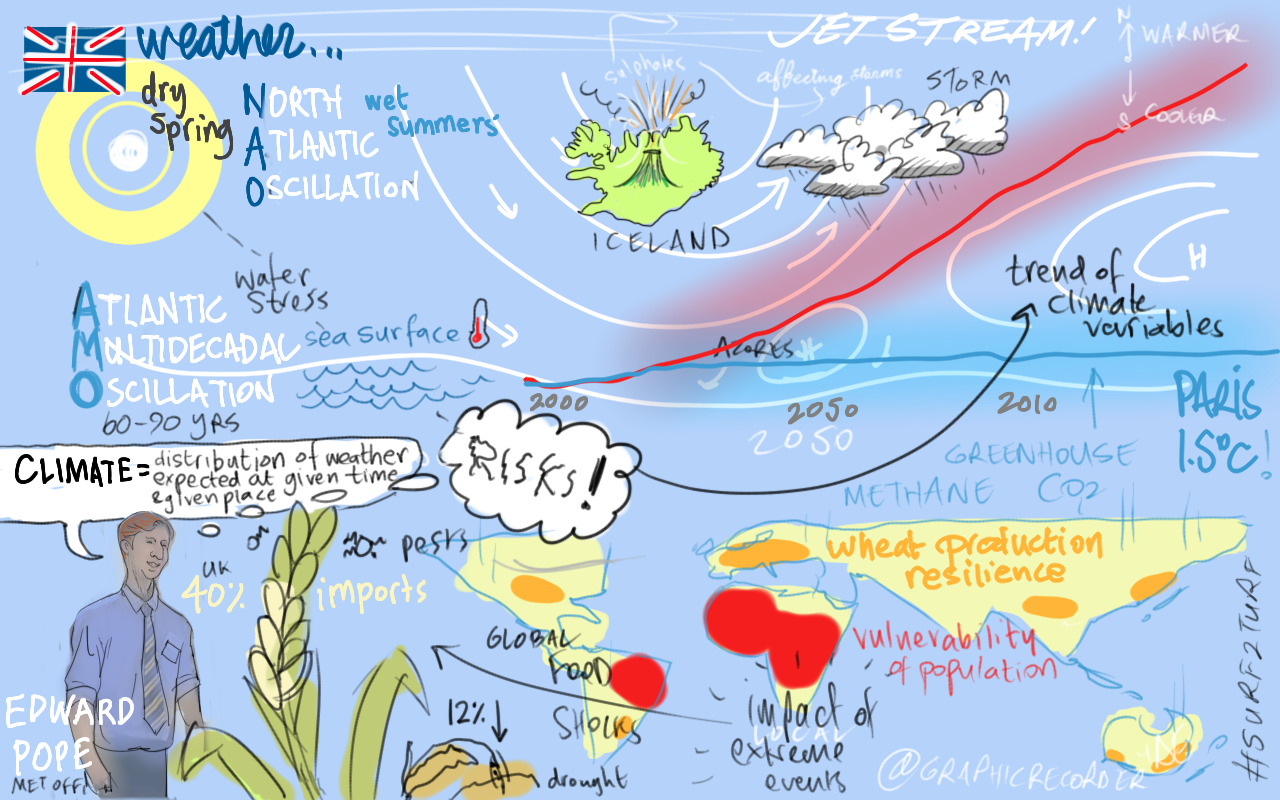

In the fish, crop and chicken systems considered there are vulnerabilities to anticipated climate change and climate variability.

The consequences of these changes for food production globally were discussed by Dr Edward Pope from the Met Office. He said this may mean that some geographical regions become less suitable for the species we currently farm and we will have to be adaptable and plan for anticipated changes.

Professor Geoff Squire from the James Hutton Institute presented his ideas on sustainable de-intensification in which he advocated moving away from breeding plants to maximise yield towards enhancing robustness to variability. He described a number of projects being carried out at the James Hutton Institute, which range from sustainable cropping rotations to biotech crops such as blight tolerant potatoes.

Looking forward

Over the course of five workshops we had some fantastic interactions, and our thinking extended to several different areas. These included genetics and disease control.

With respect to genetics, selective breeding, genetic modification and gene editing are technologies being used in both terrestrial and aquatic systems.

In terms of disease control, disease risk and emerging diseases are problems in both arenas – mathematical modelling, breeding for resistance and improved biosecurity are relevant to both and the similarities between them mean that solutions in one arena could be applied to the other.

I look forward to taking forward some of the ideas on this muddy terrestrial/aquatic interface. As a mathematical biologist, I can’t deny my personal favourite is the idea of developing resilient systems which will minimise losses in the more variable environment that we are now subjected to. There is definitely some cool mathematical modelling to be done and some meaty research questions to be answered.

In addressing food security challenges, we need to take a whole system approach and facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations between groups who have, until now, largely worked independently.

You can watch a video featuring some of the workshop attendees.

Follow Rachel on Twitter: @AFSRachel

About Rachel Norman

Professor Rachel Norman is Chair of Aquatic Food Security at the University of Stirling. Her background is in mathematical models of infectious disease dynamics and control, particularly in wildlife systems. She moved into her post in food security in 2013 and now heads the Centre for Aquatic Food Security at Stirling.