Failure to tackle food demand could make 1.5°C limit unachievable. Global Food Security programme Champion Tim Benton and Bojana Bajželj from WRAP explain.

In Paris in December last year, 195 countries agreed to try and keep global temperature rise to “well below” 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and to “pursue efforts” towards 1.5°C.

Many had expected the 1.5°C temperature goal to drop out of the draft text during the fortnight of negotiations. Now, as the dust settles after the landmark agreement, scientists are grappling with the feasibility of meeting this more ambitious target.

But there was one sector that was largely absent from the talks in Paris. It’s something that we rely on everyday, and continuing to ignore it could mean waving goodbye to that 1.5°C goal. It’s food.

30% of emissions

Agriculture and the production of food, or “agri-food” for short, is a very significant emitter of greenhouse gases. Producing our three square meals a day causes emissions of CO2 through agricultural machinery and transporting crops and animals, nitrous oxide from the use of fertilisers (synthetic and manure), and methane from livestock and flooded paddy fields for rice.

Furthermore, the demand for food has led to global expansion of farmland at a rate of about 10M hectares per year during the last decade. Some of this cleared land is – or was – tropical rainforest, adding more emissions and reducing the capacity of land to absorb and store carbon.

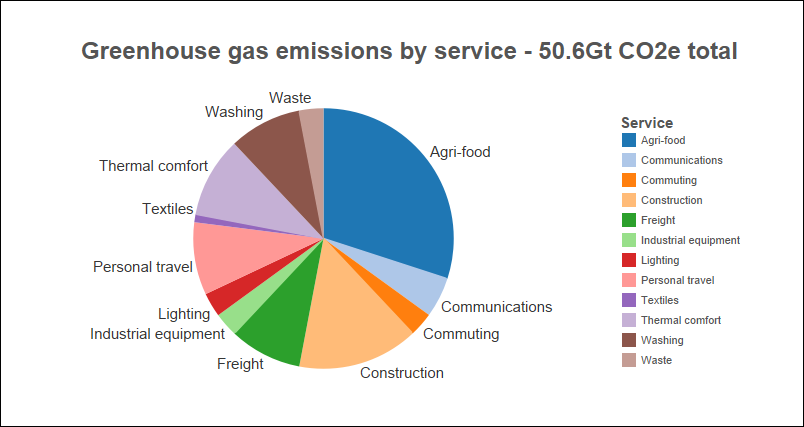

When you consider emissions according to the services we use on a day-to-day basis, agri-food accounts for approximately 30% of all greenhouse-gas emissions. As you can see from the chart below, that means producing and cooking the food we eat causes approximately the same amount of emissions as those from personal travel, lighting, heating and air conditioning, and washing machines put together.

Rising demand and emissions

During the mid-20th century, global food production benefitted from a ‘Green Revolution’, where improvements in farming technology across the world gave a huge boost to crop yields. But, more recently, there has been a worldwide deceleration in yield growth of major crops.

At the same time, as the world’s population grows and becomes richer, the demand for food is expected to increase by 60% or more by 2050 (PDF). Given recent trends, demand is likely to rise more quickly than supply towards the middle of the 21st century. This will increase pressure to convert land for farming.

Putting these drivers together suggests that emissions from agri-food will continue to grow. Changing farming practises could offset some of this increase, but achieving such changes is easier said than done.

A paper published this week, for example, reviews the various ways we can cut emissions from raising livestock. Options include using feed additives to reduce how much methane is created in the stomachs of animals, and sequestering carbon in the soils of grasslands where they graze. But limited take-up of new farming methods and high costs means that less than 10% of what is technically possible is currently economically viable.

So what does this mean for keeping temperature rise below 1.5C?

The emissions pathway we’d need to follow for a 66% chance of staying within 1.5C suggests that food-related emissions at current levels would take up our entire greenhouse gas budget in 2050.

That means unless things change – radically – our demand for food could leave no space for emissions from any of the other services we require to live our daily lives. In short, our demand for food alone could virtually guarantee that the Paris aspirations are unachievable.

Where to start

There are three possible ways we could respond to this sobering conclusion:

- We carry on as we are and miss the Paris targets, and therefore perhaps lock us into 4-5C of global warming by the end of the century

- We rely on research and innovation to find ways to significantly increase yields to reduce the rate of land conversion and develop carbon capture and storage, or

- We recognise that demand for food is driving emissions and work to change that to meet the supply-side improvements halfway

The first option is unthinkable. The second has possibilities, but there is little sign of research budgets on the scale necessary being deployed, and furthermore, there is a significant gap between mitigation potential and economic viability. The third option seems, at least initially, a no-brainer.

We know our habits have changed rapidly in recent decades – we buy more, buy more cheaply, eat differently, waste more – but could it change again to achieve a ‘low carbon food lifestyle’? There are a few places we could start.

First, reducing food waste. On a global basis, about a third of food is lost in fields or storage, or wasted in the supply chain and home. Throwing away food doesn’t just waste valuable resources, but also causes additional emissions when ending up in landfill. Food waste costs the average UK family with children £700 per year.

Second, cutting down on consumption of intensively-produced meat and dairy. Raising livestock is a much less efficient way of producing food than growing crops. Currently, a third of the crops we grow is fed to livestock to produce meat, and nearly half of the emissions from agri-food are related to meat production – more than the entire transport sector.

If we used the land growing feed to grow food, and ate only meat from pasture-fed animals, there is scope for very significant reductions in emissions. If we stick with non-pasture fed animals, then the choice of meat is important – producing beef emits more than five times as much as chicken and pork.

This ties with a third change – eating a healthy diet. Increasingly, people around the world eat more calories than are good for them (about two billion adults are overweight or obese). In Europe, for example, we eat around twice as much meat as is deemed healthy, while in the US it’s three times. Another paper published this week suggests that a global switch towards more plant-based diets would reduce global mortality by up to 10% and food-related greenhouse gas emissions by as much as 70% by 2050.

Putting all these factors together could reduce global food demand by a third or more, and that’s without considering ways for agriculture to become more efficient and higher yielding.

It means that adjusting our diets and attitude to waste has the potential to bring the Paris targets back in sight.

This blog post originally appeared on the CarbonBrief.org website.

About Tim Benton

Tim Benton is GFS Champion and an interdisciplinary researcher working on issues around agriculture-environment interactions. Formerly, he was Research Dean in the Faculty of Biological Sciences, University of Leeds, and Chair of the Africa College Partnership, an interdisciplinary virtual research institute concerned with sustainable agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa. He has worked on the links between farming and biodiversity (and ecosystem services) for many years.

About Bojana Bajželj

Bojana Bajželj is interested in global food security, climate change and land use. Her research points to the importance of addressing food waste and sustainable diets from climate mitigation perspective. Before joining the University of Cambridge, Bojana worked as environmental consultant. She holds an MSc in Environmental Technology form Imperial College London and a degree in Landscape Planning from the University of Ljubljana.

Great post…..the article is very informative and educative, I love the images of the site.Thanks

Many thanks. Very much appreciate the positive comment. I am currently in Brussels where we have been talking about this issue; raising it – and making it an issue – is the first step to getting positive recognition of the need for change.

Thank you very much, the world should know that Africa is not able to survive without true help and education. United Nation should sponsor your program to educate Africa on this. How can we be part of your education team? thanks