Complex supply chains permeate even local products.

Take a typical biscuit-containing chocolate bar from a British shop, manufactured in a British factory. It contains sugar, cocoa, milk, whey, wheat, yeast, salt, palm oil and calcium sulphate (a nutritional additive) which are sourced from all over the world. For instance,

- salt may come from China

- calcium sulphate from India

- palm oil from Southeast Asia

- whey from New Zealand

- milk and wheat from the EU

- sugar from the Caribbean

- cocoa for the actual chocolate from South America

Even less manufactured foods such as breakfast cereals may contain many ingredients from around the world. The bulk of a fruit-containing cereal may be indigenous to the UK, but the dried apricots, cranberries and raisins will come from overseas, as will the Brazil nuts and other nuts in muesli-style cereals.

Furthermore, many people like to chop banana on top of their flakes, which are typically from tropical climates, and some use orange juice instead of milk, which is also likely to come from warmer countries.

This goes for many foods, to say nothing of the (once) exotic herbs and spices that adorn our plates. Hence much of what we eat comes from abroad, or contains ingredients sourced globally, even when the factory is based in the UK.

Where does my food come from?

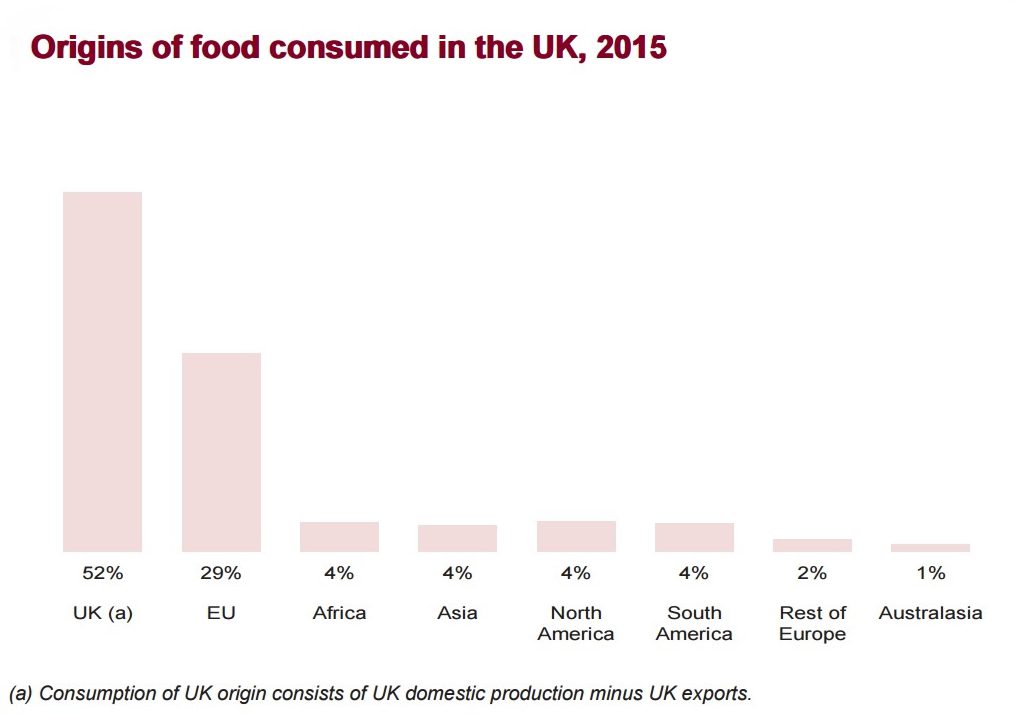

Globalisation and the profusion of ‘world food’ shops and specialised aisles for foreign favourites indicate that food from abroad is a fact of life for UK consumers. However, most food is sourced from the countries closest to us for obvious reasons – proximity means lower transportation costs, extra freshness, and we also have historically similar cultural tastes.

Unsurprisingly, this is a pattern likely to be repeated for all individual nations across the world.

Based on the farm-gate value of unprocessed food in 2015, the UK supplied over half (52%) of the food consumed in the UK. The leading foreign suppliers of food consumed in the UK were countries from the EU (29% of the food consumed in the UK) and Africa, Asia, North and South America (all providing a 4% share). Two countries accounted for 69% of UK imports of fresh vegetables. Three countries accounted for 54% of unmilled wheat imports, and four countries accounted for 44% of UK imports of fresh fruit.

It is worth noting that around 160 countries make up a significant portion (about 12%) of our food imports – making the UK’s tastes truly global and integral to the world economy.

Sourcing food from a diverse range of stable supplying countries enhances food security because shocks and surprises in the food production network do not equally affect every country at once. We need to produce ‘enough’ food in the UK to guard against shocks abroad, but at the same time have a diverse range of supply from abroad in case we experience food shocks here.

A wide food import web means that more energy is expended bringing food to the UK. This has become a more prominent issue following the Paris Agreement, due to greenhouse-gas emissions exacerbating climate change, which is widely predicted to negatively impact world agriculture. However, total emissions depend on the product in question – GHG emissions are lower overall for tomatoes grown in the warmer climes of Spain using natural sunlight and then imported to the UK, versus tomatoes grown locally in heated glasshouses. This life cycle analysis is a more important measure than food miles on their own.

Information sourced from Defra and the British Retail Consortium.